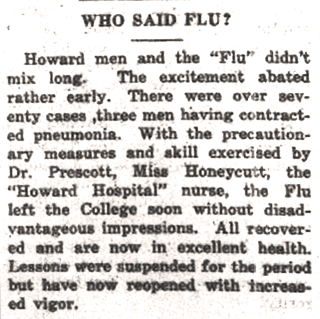

The Crimson article, Howard College

The Crimson article, Howard College

Like the pandemic we are currently experiencing with COVID-19, the world was changed by the Spanish Flu Epidemic. Reactions in the modern era are like those in 1918: public gathering places such as theaters, schools, and churches were closed, and people were encouraged to stay in their homes. Unlike today, news and people traveled slowly.

The first reported case of Spanish Flu in the United States was at a U.S. Army Camp in Kansas during March of 1918. The first case of the disease in Alabama was in Huntsville during September of that year. The virus was peculiar in that it struck, and was deadly to, people of all ages. In contrast, the typical disease is more likely to specifically affect younger and older people. During that time, there was no flu vaccination, and the discovery of penicillin was still 10 years away. Medical professionals were stretched even thinner than usual due to WWI still raging as the flu spread to every single community.

Both rural and urban areas were affected by the highly infectious disease, and it spread at unprecedented levels. At first, Birmingham officials were hesitant to admit that the flu had made it to town. On October 4th, Health Officer Dr. J.D. Dowling stating that there was no Spanish Flu in Jefferson County; though, reports indicate that up to 500 had been infected, and there were several deaths. By October 7th, the Birmingham Board of Health decided it was too dangerous to ignore this fast-growing problem and recommended that all “places of public assembly” be closed. The Birmingham and Jefferson County School Boards immediately closed schools for two weeks following the recommendation. On October 8th, the Birmingham City Commission passed a resolution ordering the closure of all public meetings. This included churches, Sunday schools, and the state fair. Already, Birmingham hospitals were at full capacity. So, Central High School and Colored Industrial High School were converted to segregated emergency hospitals. The death toll continued to rise to a single day high of 31 on October 18th. It is unknown how many people were killed by the disease. For citizens of Birmingham, hospitals and doctors were available in town, but this was not the case for most Alabamians-who lived in rural communities.

Howard College was affected like the rest of the world but was exceptionally lucky. According to an article in the school newspaper, The Crimson, the school halted classes with the rest of the city and tended to 70 students who contracted the flu. Thanks to the on-campus medical professionals Dr. Prescott and nurse Miss Honeycutt only 3 of these cases resulted in pneumonia and almost unbelievably there were no deaths.

Those that did not live close enough to be seen by a doctor were cared for by family members and neighbors. Some communities were so isolated, it would require a day or more of travel by wagon to see a doctor, and the sick may no longer be alive upon arrival to that doctor. In these communities, the dead were buried by their neighbors in the same clothing they died in. Some communities experienced such a volume of loss that victims were buried in mass graves. Because of this, there is no way to know how many Alabamians were stricken with the flu, but in the last two weeks of October of that year, over 37,000 cases were reported across the state.

Birmingham was able to reopen by November; city schools began classes November 4th. This coincided with the end of WWI on November 11, 1918. There was another small uptick of flu cases after the armistice celebrations, but the flu had essentially finished with Alabama by February, 1919. The world was able to recover from this deadly flu outbreak, but it has never been forgotten. While the deadly “Spanish Flu” no longer exists, scientists have determined that all strains of seasonal flu descended from this flu. 102 years on we are lucky to have modern medicine available and a hospital within a short drive of any county in Alabama. Until this global pandemic runs its course, let’s all take a note from 1918; stay at home when able and care for our neighbors.

Resources

- “1918 Flu Outbreak,” Alabama Department of Public Health, updated August 24, 2018, https://www.alabamapublichealth.gov/pandemicflu/history-of-1918-influenza.html.

- “1918 Pandemic,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, updated March 20, 2019, https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/1918-pandemic-h1n1.html.

- “Birmingham, Alabama, Influenza Encyclopedia,” University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine, accessed April 3, 2020, https://www.influenzaarchive.org/cities/city-birmingham.html#.

- “Discovery and Development of Penicillin,” American Chemical Society, accessed April 3, 2020, https://www.acs.org/content/acs/en/education/whatischemistry/landmarks/flemingpenicillin.html.

- Kazek, Kelly, “How the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic changed Alabama,” al.com, updated January 30, 2019, https://www.al.com/living/2018/01/how_the_1918_spanish_flu_pande.html.

- “Who Said Flu?,” The Howard Crimson, November 11, 1918, https://digitalcollections.samford.edu/Documents/Detail/1918-11-11-the-howard-crimson/182.